Photo essay: Lessons in climate resilience

This article was originally published on India Development Review and can be viewed here.

India ranks seventh among the countries vulnerable to climate change. According to the Climate Vulnerability Index, 80 percent of India’s population lives under constant risk of a climate disaster. In 2020 alone, nearly 14 million Indians migrated because of the slow onset impacts of climate change events. This number might more than treble by 2050 if global temperatures increase to 3.2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

As the effects of droughts, floods, and cyclones intensify, more people are likely to lose lives and livelihoods. However, communities and individuals across India are building climate resilience by embracing nature-based solutions and traditional wisdom in response to the changes in their environment. This photo essay captures the impact climate change has had on people living in some of India’s most climate vulnerable states such as Kerala, Maharashtra, Odisha, Rajasthan, and Uttarakhand, and how they are rebuilding their lives amid the adversities.

Photo Credit: Shawn Sebastian

Jayachandran and his daughters sit in front of their new home in Kerala’s Idukki district. After their house got swept away during the Kerala floods in 2018, Jayachandran constructed this home with the help of a government scheme, which provided INR 10 lakh (approximately €11,330).

Photo Credit: Shawn Sebastian

Shiv Prakash and his family live in Govindpura, a village near Jodhpur, Rajasthan. Until the early 2000s, Govindpura, with over 250 households, suffered the dual challenges of seasonal flash floods and recurring droughts. Over time, the villagers worked with a local nonprofit to build structures, such as check dams, to stop the gushing water and replenish groundwater.

Photo Credit: Shawn Sebastian

Members of a women’s collective gather around a patch of forest scorched by one of the several wildfires that has ravaged Sitlakhet in Uttarakhand’s Almora district. As the frequency of forest fires has risen sharply in recent years, the mahila mangal dal (women’s welfare association) now works closely with the state forest department officials in fighting these forest fires early, primarily using branches of trees.

Photo Credit: Shawn Sebastian

Yogambar Singh Rawat, a retired school teacher in Uttarakhand’s Rudraprayag district, tunes into a community radio station, Mandakini Ki Awaz. The station focuses on building community awareness about disaster risk reduction and response along with relaying timely government advisories.

Picture courtesy: Shawn Sebastian

A farmer from Belpada village in Odisha’s Kendrapara district where an indigenous variety of paddy called pottiya–which thrives in excess water—is cultivated. Having faced enormous crop losses in successive floods, farmers in the region want to cultivate more pottiya instead of hybrid paddy varieties.

Photo Credit: Shawn Sebastian

Thomas Joseph points at the raised foundation of his new house. A resident of Kerala’s Kuttanad region, which has the lowest altitude in India, Joseph rebuilt his house on pillars as the frequency of flooding has increased considerably in this region in recent years.

Photo Credit: Milan George Jacob

Rajendra Sitaram Khapre, a farmer from Maharashtra’s Ahmednagar district, buries an earthen pot beside a pomegranate plant. This traditional technique aids moisture retention from drip irrigation so that the plant can survive the scorching summer in one of India’s most drought-prone districts.

Photo Credit: Milan George Jacob

Youth groups along with community members from Ambojwadi, a slum in north western periphery of Mumbai, gather to discuss the climate crisis. With the help of a local nonprofit, they have mapped out areas in the settlement that are prone to flooding, and devised a quick response strategy in case of an extreme climate event.

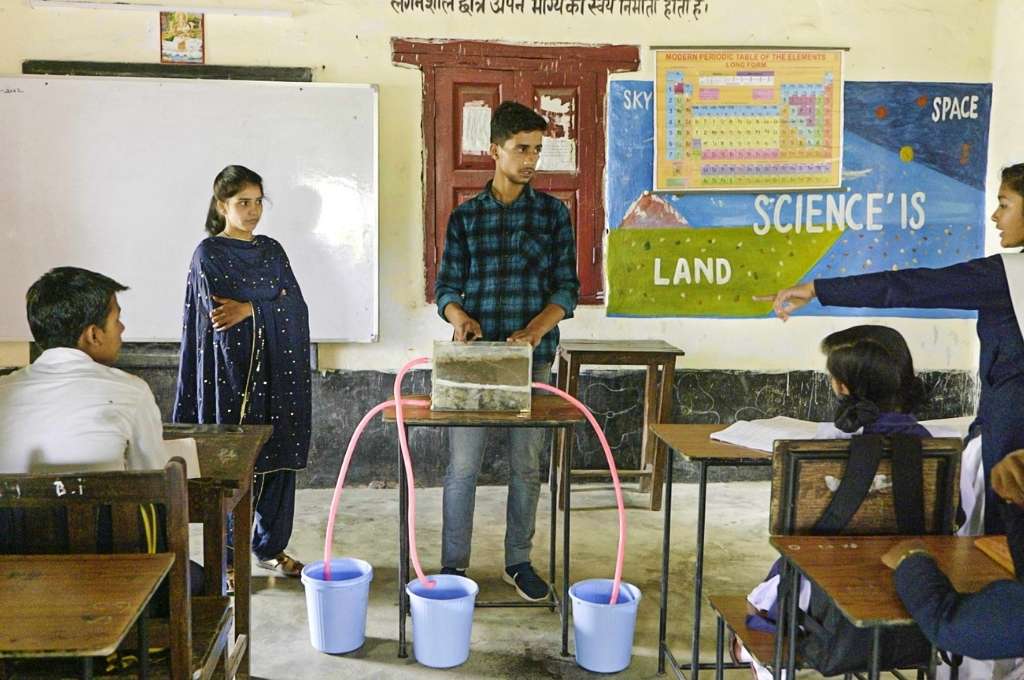

Photo Credit: Shawn Sebastian

Heera and Chandan demonstrate water conservation and spring recharge techniques to school students in Suda village of Nainital district in Uttarakhand. As the state faces water scarcity due to changes in rainfall patterns, they are leading efforts to improve spring discharge in the village. They do this by mapping and digging water recharging pits in catchment areas, which helps improve groundwater recharge, leading to increased discharge from springs.

This photo essay is part of Faces of Climate Resilience documentary project by Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) in partnership with India Climate Collaborative, EdelGive Foundation, and Drokpa Films.