Residents lead the way in reducing vulnerability of informal settlements in Kenya

Address structural inequalities

Build understanding

Collaborative action and investment

Devolve decision making

Flexible programming and learning

Invest in local capabilities

Organization: Multiple, including local government and Akiba Mashinani Trust

Donor: Multiple

Beneficiaries: 400,000

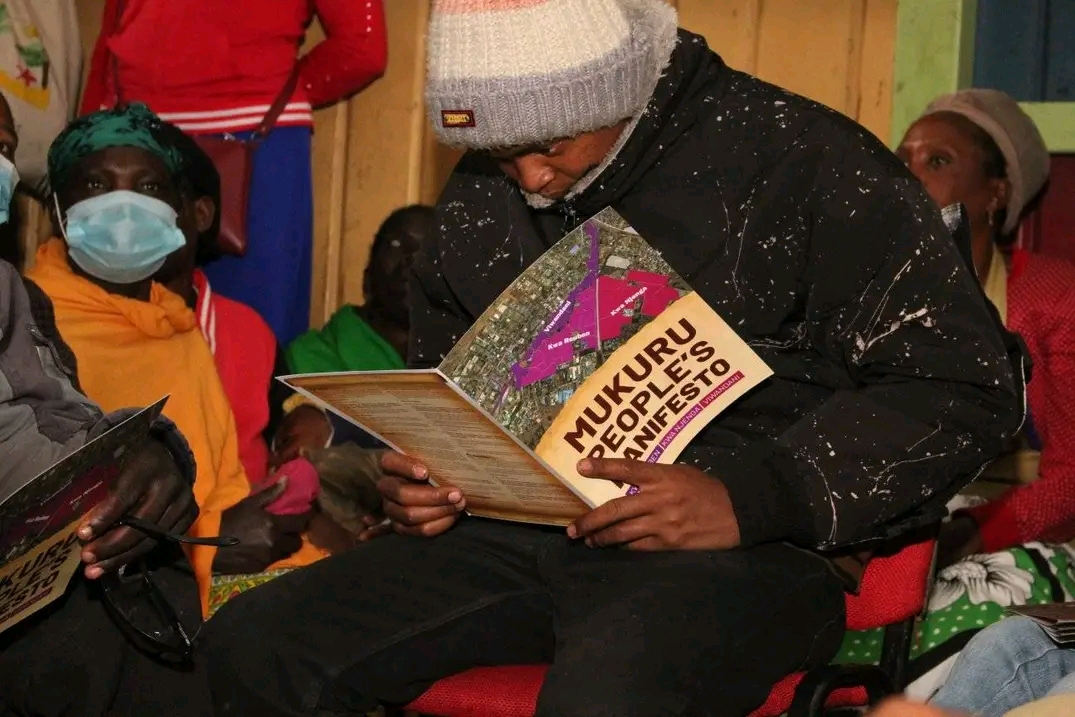

Photo credit: Akiba Mashinani Trust

In one of the largest informal settlements in Nairobi, thousands of people living in informal settlements are increasing their resilience to climate impacts thanks to locally led efforts to address vulnerability.

Everyday life for the 400,000 people who call Mukuru home is not easy. The slum, situated in the east of the Kenyan capital, Nairobi, has high levels of poverty, and limited access to basic services like water and sanitation, and poor housing. These challenges are exacerbated by climate change, with residents highly vulnerable to multiple climate hazards such as extreme rainfall, floods, water- and vector-borne diseases, and extreme heat, fires and water scarcity. During a heat wave in Nairobi in 2015, for example, informal settlements were 3-5°C hotter than other parts of the city.

The constant threat of eviction for Mukuru’s residents dates back several decades when land was gifted to select individuals due to political patronage. This led to the formation of the Muungano alliance to seek legal recourse. This alliance was created by three organizations: Muungano wa Wanavijiji’ (Kiswahili for ‘united slum dwellers’); Akiba Mashinani Trust (AMT), a fund for the urban poor; and Slum Dwellers International Kenya, an NGO that provides professional and technical support.

The Muungano alliance quickly realized that stopping evictions alone was not enough, as the living conditions in Mukuru were totally inadequate and posed a serious danger to human health. In 2014, AMT, with a grant from the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), and a team of action researchers from University of Nairobi, Katiba Institute and Strathmore University, documented the deeply marginalized conditions in which residents lived. The alliance demonstrated that Mukuru’s residents were effectively forced to pay a ‘poverty penalty’ for the services received from informal service providers. Water cost nearly four times more than elsewhere, electricity double as much, and rent per square meter was 20 percent higher than that paid by residents living in formal housing areas in Nairobi.

Framing Mukuru’s informal settlements as a KSh 7 billion (approximately USD 63.5 million) economy, in addition to underlining residents’ ability to pay for public services, helped to get the attention of the Nairobi County Government. Political events (such as the 2017 general elections) were used to rally support and build strong local ownership from the start. Full local government support followed, with Mukuru being declared a ‘Special Planning Area’ (SPA) in 2017, which provided flexibility in city planning regulations on account of Mukuru’s special circumstances, setting in motion a locally led process for developing a Mukuru Integrated Development Plan. Key was the local government’s recognition that the upgrading process was a challenge for the whole city of Nairobi, with the integration of the Mukuru plan into Nairobi’s 20-year City Integrated Development Plan.

Framing Mukuru’s informal settlements as a KSh 7 billion (approximately USD 63.5 million) economy, in addition to underlining residents’ ability to pay for public services, helped to get the attention of the Nairobi County Government. Political events (such as the 2017 general elections) were used to rally support and build strong local ownership from the start. Full local government support followed, with Mukuru being declared a ‘Special Planning Area’ (SPA) in 2017, which provided flexibility in city planning regulations on account of Mukuru’s special circumstances, setting in motion a locally led process for developing a Mukuru Integrated Development Plan. Key was the local government’s recognition that the upgrading process was a challenge for the whole city of Nairobi, with the integration of the Mukuru plan into Nairobi’s 20-year City Integrated Development Plan.

Mukuru subsequently saw the most significant upgrading of an informal settlement in the world. The approach is considered ground-breaking as from the very start it sought to engage Mukuru’s residents in a community-wide planning process for the provision of basic services. Savings groups were used to engage communities, with tools such as community-led data collection utilized to map the area. This provided a better understanding of the challenges faced, which in turn helped the local community to make evidence-based arguments for the provision of local services.

To ensure that all residents participate, ten households are grouped into a ‘cell’, with a total of 10,000 cells across Mukuru. Ten cells are further grouped into 1,000 ‘barazas’ (or sub-clusters), which in turn are grouped into 13 different segments. This local action is bolstered by a team of community mobilizers, who all receive training to facilitate community engagement.

Mirroring the different Nairobi City County departments, seven sectors were identified as priorities for action: housing, infrastructure and commerce; education, youth affairs and culture; health services; land and institutional frameworks; finance; water, sanitation and energy; and environment and natural resources. To ensure that the planning process for each sector has adequate technical support, technical experts from 44 organizations (representing local government, academia, and international and local NGOs) are grouped into seven ‘consortia’, each led by personnel from Nairobi City County. Accountability is enhanced through the use of tools such as photographs and reports to ensure that all perspectives are reflected in the sectoral plans.

The planning process was not without concern from residents, some of whom feared it was merely an innovative way of evicting them, and private service providers, who saw it as a threat to their businesses and livelihoods. These concerns were addressed through discussion and debate in the barazas and the use of community radio.

While it is still early to judge the lasting resilience impact of the planning process, over 50 kilometers of roads are already under construction in Mukuru, infrastructure such as stormwater drains are being laid, and each plot is being connected to electricity, safe and free water, and the sewerage network. The Mukuru planning approach was endorsed by the former President of Kenya, Uhuru Kenyatta, and is now being replicated in Kibera and Mathare, two other informal settlements in Nairobi, in addition to inspiring similar projects in informal settlements across Africa and Asia.

Across Africa, more than half the urban population lives in informal settlements that are similar to Mukuru, characterized by high levels of poverty, fragile and dangerous conditions, and a lack of risk-reducing infrastructure and support. National and sub-national decision-makers often fear that tackling the problems within them will lead to the granting of formal rights to informal residents, while funders view projects in informal settlements to be a high risk from an environmental and social impact risk perspective. Replicating and scaling up the Mukuru planning approach, with a stronger climate resilience component, could provide a solution to the complex problem of reducing the climate vulnerability of millions living in informal settlements across the continent.